Looking for Duras weaves three strands of memoir into one: my lifelong infatuation with the French writer Marguerite Duras, a journey through Vietnam and Cambodia tracing her footsteps, and a musing on mothers and melancholy. (Read prev chap here).

Back at the Classic St Hotel Mr TF greets me like an old friend. Unpacking in my old room I instantly miss the ambiance of the past couple of days, but my evening is already planned. As promised Ngat, my poet friend, has arranged an early dinner date for me to meet her women writer friends and I have just enough time to shower and dress before they come to meet me at my hotel.

In the tiny lobby filled with the antiques and sculptures of mystic animals carved from gnarly tree roots, I find Ngat and her friends sitting, waiting, perfectly on time. Tran Thi Truong,* the same age as Ngat and myself, is a well-known journalist, novelist and short story author. She is a bit taller than Ngat, and has the look of an experienced journo always on the hunt for a story. I can easily see her on the newsroom floor, fighting for attention on women’s issues. DiLi (Nguyen Dieu Linh) * is an attractive young woman and quite a celebrity it seems, who as well as being a journalist and blogger is Vietnam’s first female writer of popular crime and horror fiction. There is not an ounce of bookishness about her stylish orange pants suit as she leads the way on foot through the busy evening streets to an anonymous looking doorway of a building a couple of blocks away. A mirrored lift takes us three stories up to the Lake View Restaurant. It is still light so we choose an open-air table overlooking the dusk-lit green lake. I choose authentic Hanoi phó (noodle soup) and the others opt for pasta —spaghetti bolognese, ravioli and cream fettucini. I have to chuckle when I see the Vietnamese version of Italian dishes arrive looking flat and uninspiring, but they are to all reports, tasty.

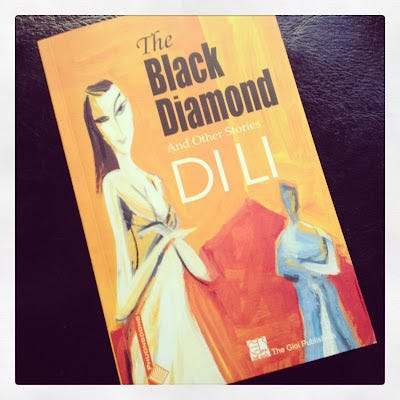

We swap books again and chat a bit about our lives as writers. Having spent some time living in Europe and the US, Truong is committed to helping Vietnamese women achieve equity in gender roles. Working within the limits imposed by her government she has found story telling to be a particularly effective tool. DiLi and Truong have a collection of bi-lingual short stories coming out soon and DiLi gives me some of her books to add to those I already received from Ngat. I tell them of the literary festivals I have been to in Asia and promise to put a word in for them. DiLi works for an arts magazine and asks if we can do an online interview about my writing. I laugh and tell her I am by no means famous but would be delighted. At some point I mention my Duras pilgrimage. Intent on enjoying their pasta, they simply nod and our talk moves on to other things. I feel too self-conscious to bring it up again and a bit embarrassed that I might be just another Duras fan arriving on their shores with little knowledge of Vietnam’s own literary heritage. In Australia I’d admired Australian/Vietnamese writers like Nam Le (whose book of short stories called The Boat enjoyed huge success and contributed to bringing the short story form back into popularity). And the Vietnamese born Viet/American poet Mong Lan ( we met at Ubud Writer’s and Reader’s Festival) whose work deals with the experience of her own and others displacement, but I know little about contemporary Vietnamese writing. The meal over, I feel my opportunity slipping away as I watch the questions I might have asked evaporate into the humid night air.

As we are about to leave Ngat asks me if I have seen the Water Puppets yet. I’d noticed the grand Thang Long building on my walks but admit I haven’t been in for the show. In a flash they bustle me out of the restaurant and around the corner to the famous theatre. Ngat enquires, buys my ticket and practically pushes me in the door to catch the last show of the day. We wave our goodbyes and I enter the darkened auditorium as the music begins.

Fumbling about for my seat, my paranoid self wonders if they really did have places to be or they genuinely wanted me to have an authentic Vietnamese cultural experience. Whatever the answer I decide it was traveller’s luck to have met these three interesting women. Although brief, our meeting has given me a glimpse of the everyday strength and determination these writers possess as they champion the cause of Vietnamese women. It can’t be an easy task in a traditional communist-run society where censorship rules. And yet in The Defiant Muse, the book Ngat had given me, I’d learned that the tradition of combining the literary arts with the military arts started with a female martial arts hero Trúng Trác. I learned too how Vietnamese poetry * is rooted in the daily language of ordinary Vietnamese people and that the tradition of orally transmitting short lyric poems (ca dao) is over a thousand years old. MD would surely have been aware of this. Maybe it’s no coincidence that the first writing she penned was poetry.

As the lights come up I realise that the stage is in fact a pond and I am about to experience a classical form of oral storytelling traditionally performed by peasants of the northern regions. Originally staged during rice harvest celebrations the water puppet opera would take place in a large area of water or rice paddy in front of a temple structure hung with brightly coloured brocades. Here the configuration is created indoors with a higher platform to one side where male and female musicians in traditional dress sit cross-legged at zithers and percussion instruments. This cast of players have clearly done thousands of shows. The musicians look like they can play in their sleep, in fact some of them look like they are asleep with wonderful lines of boredom etched into their tired faces. It doesn’t detract from the wild splashing narratives played out by puppets on the water stage: dragons, tortoises, kings, queens, princes, princesses, horses, peasants, soldiers, dragonflies, flags, flowers, trees, sea creatures, wise men and more. I love watching the hyperactive creatures leaping in and out of the pond, submerging, re-emerging, as comfortable in air as they are in water. At the end when the hidden puppeteers wade forward to take their bows, the image of a nation of people up to their waists in water stays with me.

Walking back to my hotel past the lake I can’t help imagining it coming alive after midnight in a splish-splash extravaganza with Vietnamese characters riding around on the backs of sacred turtles. MD is in there too, rising up from the bottom of the soupy green lake to make her presence known.

After sleeping in until around eight I still have time for more exploring before my flight to Ho Chi Minh City later in the day. I eat some breakfast downstairs then head out for a walk around the shopping streets I didn’t get around to the other day. Spreading out from the other end of Hoan Kiem Lake, each street specialises in just one commodity and is named as such — Shoe St , Teddy Bear St, Chinese herbs, cooking pots, silver, lanterns and so on. I’m still on the lookout for MD’s villa, but the houses along these streets are such a mish mash of advertising signs, awnings and stacks of whatever product they are selling, it’s impossible to ascertain what was once there. I find myself in a small lane where shops sell every kind of savory cracker ever made — packaged in tins and packets they are stacked like a giant art installation against a yellow wall. Further along, what looks like an open-air temple glittering in red and gold, is instead a group of shops selling temple paraphernalia. Around the corner and down a bit, a line of shops are hidden beneath stacks of tall bamboo poles lined up all along the frontage. There are rope shops and straw mat shops and with enough welcome mats on display to service the whole city. Street vendors are out on their bicycles with shoulder baskets filled with dragon fruit, frangipani blooms and delicious breakfast delicacies.

I turn into Hang Gai (Silk) St, and find it already alive with shoppers. Here you can be measured up in the morning for a raw silk suit and have it delivered to your hotel by evening. Wandering deep into one of the shops on the pretense of searching for a particular silk, I notice the back part of the shop house opens up into a courtyard with living areas beyond. Perhaps it wasn’t a French villa MD’s mother owned here. Maybe it was the courtyard of a shop house like this one, where the hot and bothered photo of the mother and children was taken. It is impossible to know. I linger for a moment imagining the family photo coming alive in this setting. A shop assistant appears and I tell her the fabrics are all so beautiful I can’t decide which one I want, maybe I will come back later. She shrugs and goes on sweeping.

On the way back to the hotel I come across a small bookshop. It is little more than a hole in the wall and appears to be selling mostly Vietnamese books, but it doesn’t stop me asking if they have any books by Marguerite Duras. The girl behind the counter, busy eating her breakfast phó, shakes her head. I pronounce the name again slowly, hoping for a flash of recognition.

‘English books over there,’ she says and points to a narrow shelf half tucked away behind a door.

Grateful for some help I thank her and go looking, happy to be surrounded by books and the prospect of a browse. Sadly today there is nothing on the one lone shelf of English language books that interests me and I’m about to leave when I notice a stash of French language books two shelves above. I look through them and there out of alphabetical order and the last book in the row, I spot it. The plain cover, French edition of MD’s L’Amant, (The Lover). I snatch it up and flip through. It looks and feels like the original although I am sure it is just a good photocopy. I don’t know how much I will be able to understand but I am very excited as I hand my money over to the girl, pointing to the author’s name. She gives a thumbs up and I smile back, happy with my new find.

Back at the hotel I spend the rest of the morning reading aloud — one paragraph from L’Amant in French, one para from The Lover in English. It feels thrilling, as if I am reading the novel completely fresh. I’m so caught up in reading that I don’t notice the time. Mr TF is at the door telling me it’s time to go. Luckily I’d done a good job of packing my suitcase when I woke. I throw the few remaining items in, check the room, and rush downstairs dragging my valise behind me.

Mr TF is there to wave me off and I thank him for his hospitality telling him I will be back. I always believe I will, but this time it has to be true.

The drive to Hanoi airport feels like a rewind of my arrival days earlier, only instead of a taxi I’ve taken the shuttle bus. When I find myself marveling out loud once more at the skinny height and narrow frontage of Hanoi buildings, the young Vietnamese woman sitting in front of me explains that under French rule, land tax was calculated on the width of your property frontage. This determined property boundaries, which are still in place today but Hanoi residents cleverly came up with a way around it — to go up. Extended families often just add extra levels as sons and daughters marry and need somewhere to live. It’s a great solution to the problems of high population and the rising price of real estate.

Nguyet is an architect who completed her post grad studies in Australia. When I tell her of my search for a French villa that MD may have once lived in near a small lake, she confirms my hunch that the photograph of Marie Donnadieu and her children could well have been taken in the courtyard of a shop house, especially if she had acquired it to use as a school. The deep back of the shop house could certainly be well adapted into classrooms and it would make sense that it would be situated in the old French quarter by Hoan Kiem Lake. Nguyet tells me of her interest in the old shop houses of the area, and how she wants to protect them from development. She has overseen some redesign and renovation projects for young professionals who want a living space that combines tradition with modern features. It’s nostalgia for the past but also an awareness that once the old buildings are gone, the stories of those who lived there also disappear without a trace.

I’d be happy to keep chatting to Nguyet all day but in no time we are at the airport. The busy crowds engulf us as I wish her all the best with her future projects and go in search of my check-in desk. The Jetstar logo is not so hard to find and so far my flight seems to be running on time. There’s a big group of Vietnamese high school students checking in before me. They are full of chatter and excitement, pulling things in and out of small backpacks decorated with all manner of cute hanging toys. Their teachers’ patient smiles match the students’ exuberance as they gather the info required for check-in and give instructions. It’s going to take a while.

I double-check my notebook for details of my hotel in Saigon. I’m planning to stay in the heart of Chinatown, known as Cholon. I picked this tip up from a New York Times journalist, Matt Gross, who travelled this way a couple of years before me and whose travel article * I found the day before I left Sydney. It outlines the ideal Duras Saigon itinerary —for a spectacular rooftop view, eat breakfast at Hotel Arc En Ciel’s roof garden. Next day, hire a 1930’s Citroën to drive 145 kms to Sadec on the Mekong River where the opening to Duras’ novel The Lover is set. I won’t be hiring a Citroën but I’m planning to stay at the Arc En Ciel before taking a riverboat to Sadec on my way to Phnom Penh. Sadec is significant, for in The Lover it is from here on the Mekong River ferry crossing, that the fifteen-year old French schoolgirl, meets the rich Chinese man. They get talking and he offers her a lift in his limousine. Not long after this chance meeting, the Chinese man and the girl begin their affair. If you don’t know Duras and assume this will be the story of an underage innocent being taken advantage of by an older man, you must think again, for the girl is calling all the shots.

What’s more extraordinary is that MD didn’t write The Lover until her seventieth year. Recovering from a life-threatening illness brought on by her alcoholism, she discovered some old photos at the back of a cupboard at her house in Neauphle-Le-Chateau, just outside Paris. The writing of captions for the photos, so the story goes, evolved into a fragmented narrative based on her Indochine childhood, which in turn became The Lover. Central to the novella is the image of the girl on the ferry crossing the Mekong River. Captured not by camera but by MD’s memory, * it becomes the recurring motif around which the stories and characters of The Lover unfold.

If you have seen the film, The Lover directed by Jean-Jaques Annaud, and based on MD’s book, you will be familar with this scene…

On the ferry crossing between Sadec and Saigon the girl gets off the local bus and stands at the railing to watch the waters of the mighty river flowing by. She wears a silk dress, an old one of her mother’s, sleeveless with a low neck. A belt borrowed from one of her brothers gives it some shape and a pair of high heeled gold lamé shoes bought in a bargain sale, add to her eccentric look. Her lips are painted dark cherry-red in the fashion of the time. Schoolgirl braids hang down beneath a pinkish-brown man’s hat — a fedora with a black ribbon. The Chinese man gets out of his limousine and approaches her. Elegant though not handsome, he is around twenty-seven years old and nervous. He speaks French and wears a lightweight tussore-silk suit in the European style of the wealthy. He has never seen a young white girl like her travelling on a local bus before. He offers her a cigarette but she doesn’t smoke. He asks her how she comes to be on the ferry. She says she lives in Sadec that her mother is the headmistress of the girls’ school there but she goes to high school in Saigon. He lives in Sadec too, in the big house with the blue tiles, facing the river. His family are originally from North China, his mother is dead, there’s only his father and him left now. He’s just back from two years studying business in Paris. He offers the girl a lift. She accepts. She knows what it means. From this day on she will have a limousine at her service to take her to and from school and to Cholon where they will begin their affair.

I’m so immersed in my reading that I almost miss the boarding call. As I check my boarding pass at the gate I’m aware I‘m leaving Hanoi before I’ve really had a chance to explore, although I have a sense of it now that I didn’t have before. I didn’t really find any traces of MD here, except in my imaginings and I am keen to get to Ho Chi Minh City (which everyone still calls Saigon), to begin my Duras pilgrimage in earnest.

_______________________________________________________

* More about Nguyen Thi Hong Ngat here.

* More about Tran Thi Truong here.

* More about DiLi here. I note that MD features in her list of dislikes. Now that would have been an interesting conversation!

* In 40 C.E. after their husbands were killed by the Chinese the Trúng sisters became commanders and would recite poetry before going into battle. They held the Chinese forces at bay for over a year. The Defiant Muse, Lady Borton. p 1-3

* Read the NYT article here.

* MD calls this the ‘ absolute photograph.’ The Lover p 15.

Enjoying this Jan

Now that's a dinner among women I wish I'd been at! Loved this read.