Looking for Duras weaves three strands of memoir into one: my lifelong infatuation with the French writer Marguerite Duras, a journey through Vietnam and Cambodia tracing her footsteps, and a musing on mothers and melancholy. (Read prev chap here).

With lunch over we are back on the boat as our helmsman negotiates the web of canals to a landing area somewhere back on the main tributary. Our bus is waiting, just as Mr Thao said it would be and we all pile in. Normally good with directions, I have no idea which way we were going before and where we are headed now. I imagine that if we are to make any headway today, sometime soon we will be getting on the real river. And sure enough, after weaving our way through a maze of small streets and byways, we arrive. This is no small canal, no minor tributary; this is the real thing — the mighty Mekong. The huge moving mass of muddy water in front of us is so wide we can barely see to the other side. We get off the bus and stand gaping in awe. The road we have been left on is a scrappy bit of bitumen ending at the water’s edge. There is no jetty, no riverboat waiting, nothing. We are off the beaten track in a neighbourhood of small houses nestled among fruit orchards and industrial sites. It seems odd, but we don’t question our leader Mr Thao, who promptly instructs us to collect our luggage and follow him. Veering to the left he leads us down a narrow, broken cement path. Kids come out from dirt yards of thatched houses and watch as we drag our suitcases and backpacks along the river so close on one side, we have to be careful not to slip and fall in. After a few minutes of trundling along, Mr Thao signals us to stop and wait near a little shop as he takes a call. His brow crinkled into a frown, our usually cheery leader paces up and down while talking rapidly on his phone. He has offered no explanation of what is happening, but we do as instructed, buying water, lollies and rambutan, while chatting with a pack of kids who have gathered around. A couple of older girls strike provocative poses and talk us into buying them sweets and soft drinks. When we watch them being distributed to the younger kids we wish we had been more generous.

His phone call over, Mr Thao stands apart from us looking out at the river as if doing so will conjure up our solution. It’s clear to us all that there is a problem with the boat which is supposed to pick us up. But where? There is no landing wharf, no jetty or walkway, just water lapping against chunks of polystyrene trapped in the reeds. Mr Thao takes another call then commands us to return the way we have just come. We bid our goodbyes to the kids and bump our way back up the path. To our horror when we get back to the road, our bus is no longer there. Undeterred, Mr Thao leads on. Across the bitumen onto another path that follows the river bank in the opposite direction, we trundle on. Past workshops and small factories, dragging our belongings behind us, we feel completely ridiculous. What a strange vision we must be to the workers and villagers who smile and wave as we pass. Is this what Westerners do for fun? Those who have over-packed or bought too many souvenirs too soon are suffering under the weight of their indulgence, but the end is in sight. Around another bend, a ferry terminal looms into view.

‘We will take the ferry, then taxi to Vinh Long jetty, boat will pick us up there,’ Mr Thao announces, without any further explanation.

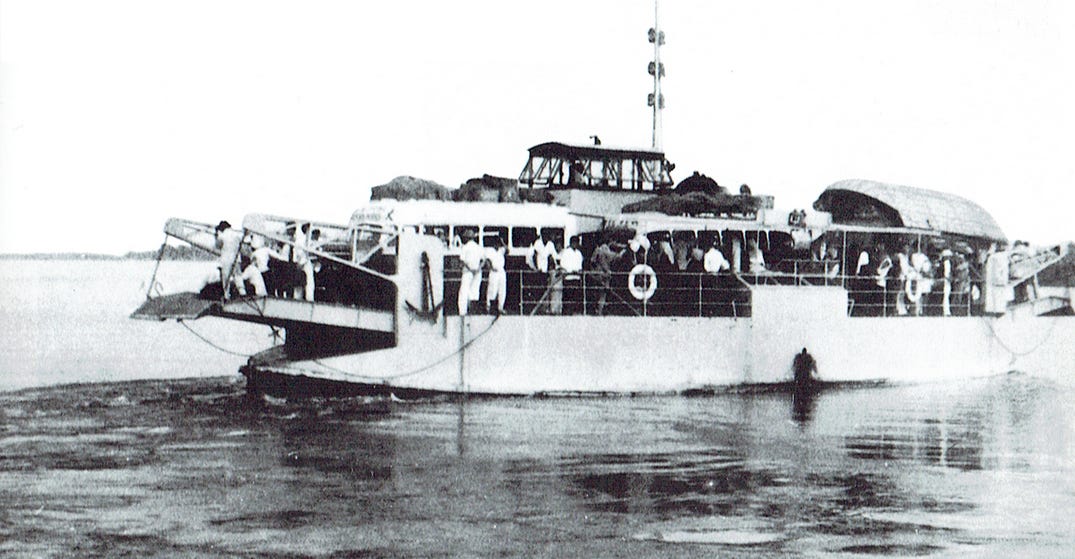

A ferry, across the Mekong! My disappointment about not stopping in at Sadec turns to elation. I had no idea there were still some ferries operating! Surely this must be one of the last and it too looks like it will be soon gone, to be replaced by the almost touching, near-finished arched structures rising from each side of the river. Of course modern ferries are much larger than they were in MD’s time, but I don’t care. I want to jump up and down on the spot at my good fortune, to cover Mr Thao in thank-you kisses, to shout my ‘woo hoos’ to the universe. Instead I smile and grin along with the others who, happy that a transport alternative has arrived, are relieved we don’t have to keep on trundling.

We are the only foot passengers and like good little tourists we file into a big open-walled shed filled with motorbike riders queuing for the next boat. On a giant screen at one end, a pop clip entertains the waiting riders— beautiful Vietnamese boys and girls float about in pastel landscapes, singing the romantic hits of the day. I watch the video for a bit, glance around the shed, then see the face of a young man looking back at me. Sitting pillion on a motorbike, he looks away shyly, then back again, holding my gaze for a long moment. The pop song builds to its crescendo as we each try to catch a glimpse into the other’s world, so different from our own.

Our mutual curiosity is rudely interrupted by a beeping, grinding noise — the gates open, the motor bike riders rev and take off out of the shed, clunking their way across the metal bridge into the bowels of the newly arrived ferry. We follow, Mr Thao yelling at us like an army sergeant, commanding us to hurry. We march onto the dock and are only metres from the gangplank when a man in blue calls out, ‘Stop!’ The ferry doors close like a drawbridge and we are left marooned, watching it sail. Mr Thao stamps his foot and waves his arms in frustration, then turns to us and gives a classic French shrug.

No matter, another vessel is on its way and in no time, we pile on board and climb the metal stairway to the open air upper deck. My pillion rider is gone but my Durasienne moment is just beginning. I lean my foot on the railing and contemplate the muddy waters swirling past. In The Lover MD writes: ‘My mother tells me never in my whole life shall I ever again see rivers as beautiful and big and wild as these… the great regions of water soon to disappear into the caves of ocean.’ *

I may be missing out on my Sadec moment, but none of it matters now. Here on the Mekong, MD is all around. I have picked up her scent, I am on her river, I am in her country now.

According to Laure Adler, Vinh Long was where MD’s childhood really began, but how they ended up there is a long story. In May 1921 when MD’s father was hospitalised in France her mother decided she and the children should remain in Indochine. I guess she was thinking he would recover like he had before but after his death just months later, Marie took leave from her teaching position in Phnom Penh so she and the children could return. They stayed in France for a couple of years but when her claims on her husband’s property near Toulouse were unsuccessful, they had no choice but to return to the colony. Marie didn’t want to go back to Phnom Penh where she had learned the devastating news of her husband’s demise, besides her former position as headmistress had already been filled. Initially she was told that she had no choice and must return to her old job, but after haranguing the authorities, Marie Donnadieu was given the position of administrative head of a girl’s school in the Mekong town of Vinh Long. It was 1924 and Marguerite, just ten years old, loved it. Living on the edges of the white area, she and her brothers went barefoot, spoke fluent Vietnamese and did as they pleased. Later in her writing she would revisit these places again and again — the tree-lined avenues, the parks and gardens leading down to the river, the billabongs and canals, forests filled with monkeys and tigers, the alluvial plains.

But in Vinh Long MD’s mother began to suffer from fits of depression. The grief of losing her husband (she still communicated with him in moments of need), the burden of being sole provider on a low wage, and the anti-social behavior of her children — all these things were wearing her down. With no father to guide them, MD’s mother seemed to have no control over her sons. Marguerite kept her head down. She worked hard at her studies, trying to avoid her older brother and shield the younger one from his constant violent threats. Marie finally sent Pierre back to his father’s region in France and put him in the charge of a catholic priest, hoping he might sort him out. For Marguerite and her brother Paulo it was a welcome respite. Free to enjoy their life without the continual threat of violence, they could be children again.

Our ferry reaches the other side and Mr Thao bundles us into taxis for the short drive through Vinh Long town. We keep to the river and I’m trying to peer down streets hoping to catch a glimpse of the tree-lined avenues MD wrote about. Among the chaotic jumble of shop fronts, it’s hard to tell how much of MD’s Vinh Long has survived. The taxis drop us off in a small riverside park next to a marina — a few skinny trees, a shady pergola and some benches for us to sit down on. I wish I could just take off for a walkabout but we are instructed to wait in the shaded area where a group of disgruntled passengers, joining us from another tour run by the same company, tell us they have been already waiting for three hours. When we ask them if they know how long it will be until we board our vessel, they have no idea and are not in the mood to surmise. I drop my bags and head across the road to buy some mangosteens from a fruit stall I noticed as we drove in. I linger about, eyeing off the other fruits but decide to keep it simple. Back at the park I set about peeling one. It is never an easy task. You have to dig your fingernails into the tough purple skin and try to extract the fruit without squashing it. An older Vietnamese woman sitting nearby can’t help but notice my clumsy efforts. She kindly demonstrates how by simply pressing at the base of the fruit, the skin breaks open and the delicious cream-coloured sections just pop out. Thanking her, I laugh at my clumsiness and offer them around. It’s then that we notice that a narrow barge-like boat, the kind you might see on European canals, has limped into dock. Mr Thao is supervising a crew of two and it looks like we are ready to board.

They ask for our luggage and start stacking it on top of the low roof. With a short length of rope they get it all secured under a blue tarp and invite us to step down into the narrow bus-like interior. The small sliding windows don’t open very far. The elderly NZ pair and I give each other raised eyebrow looks as we claim our seats. With the luggage on top and no way out below, if we capsize, we will definitely be in a pickle. It’s all too much for a European couple. They storm off the boat, retrieving their luggage with much difficulty, threatening to have words with head office which I’m sure will fall on deaf ears. They are the only mutineers, the rest of us are ready for adventure or, depending on the outcome, just plain stupid.

While we are waiting for them to repack the luggage, I spend the time cleaning out my shoulder bag. Actually I have a series of bags within bags. There’s my tough- skin Crumpler bag that can buckle down to half size and within it I usually have one or two soft cotton bags that I can pull out for carrying fruit, drinks, books or odds and ends. It never ceases to amaze me how much stuff I can collect in just a few days of travelling. As I have the seat to myself, I can lay it all out: things to keep, things to chuck. The latter I put into one of the cotton bags for transfer to a bin at a later date. I’m keeping my notebooks of course, a collection of pens and pencils, moisturiser, deodorant, hand cream, bangles and my MD books. My chuck out pile is mostly paper, brochures, business cards, boarding passes. Only at the last minute I decide to keep them as records of the trip, and make a plan to glue them into one of my plain-paged notebooks. Even the list I made before leaving ends up in the keep pile. While minimalists and anti-clutterers would call this a form of hoarding, I’m so grateful for the collection of lists and other random jottings my mother Marj left lying around her house. Her household lists were often written on the back of sketches or paintings, on used envelopes and random bits of cardboard also used for other jottings. Stuck on the fridge or left on the sideboard, there are so many I could make a book of them.

Spray and Wipe, sweet corn, pickles, 4 toilet rolls, 2 litres milk, turmeric, P Nut Butter, peppermint tic tacs, good olive oil, dried fruit, Dove soap, toothpaste, thyme, stamps, 5B pencil, bread rolls, sleeping pills, envelopes, band aids, chutney, lamingtons, LIFE IS HELL! Alfoil, apple juice, shampoo, 2 small tins sardines, Solvol, custard, cleansing cream, 2 scent packets, mince, hooks, Jex, 2 small notebooks.

MD had a similar list on the wall at Neauphle-le-Château of household things that needed to be replenished on a regular basis:

‘Table salt, pepper sugar, coffee, wine, potatoes, pasta, rice, oil, vinegar, onions, garlic, milk, butter, flour, eggs, tinned tomatoes, kitchen salt, Nescafe, nuoc mam (Vietnamese fish sauce), bread, cheeses, yoghourt, window cleaner, lavatory paper,light bulbs, kitchen soap, Scotchbrite, eau de Javel (bleach), washing powder (hand), Spontex (dishcloth, sponge), Ajax, steel wool, coffee filters, fuses, insulating tape.” *

Somehow the simplicity of these lists always moves me. In spite of the highs and lows of the writing life one must still eat, clean and fix the fuses when they blow. These two women, these two mothers, as difficult or painful as their lives may have been, carried on regardless, taking care of practicalities.

It looks like we are ready to go. I pack my things back in my bag. If we do come to grief on the river I know that everything is in its place, everything is in order.

______________

*The Lover p 14.

* Practicalities p 49.

I loved the dynamic storyline here. The tension between plans and expectations and how that might be resolved in risky settings.

Love all of this. Especially your mother’s shopping list!!!