Read Episode 1 here.

2.

I throw my small bag and suitcase on the rack provided. There’s a bedside table, a few clothing hooks on the wall and that’s about it. Who needs more when all you are going to do is sleep?

I’m not surprised Mr TF doesn’t know who MD is. How could he possibly know of my quest to find some traces of my literary icon in his country formerly known as French Indochina. And he would have no way of knowing that already I’m writing like her, using initials for real people instead of their names (including his) and adding footnotes where needed.

Why make it easy for anyone? was MD’s attitude. Why have a plot when you can have pages and pages where nothing happens but weeping and then weeping again? Why write a novel like a novel, why not write it like a film? Why not have actors in a novel reading the novel as if it were a play, while adding notes for a film director? Why not publish your most famous work, The Lover, based on your early life in Indochina, finally win the Big Prize — the coveted Prix Goncourt, then write another version of it a few years later with a new title? Why? Because you are MD and you can! If you haven’t come across the writing of Marguerite Duras before, let me remind you — MD is not every one’s cup of tea. MD is an acquired taste. Brilliant, legendary, experimental, innovative, unpredictable, difficult, contrary, narcissistic, alcoholic — these are just a few of the words used to describe her. Those of us who hail her as our hero (and there are many) don’t give a hoot. We would gladly follow her to the ends of the earth. *

I don’t have long, a few days at the most. My decision to come on this pilgrimage was a last minute thing. When my friend Sonia, fresh from her Vietnam holiday, told me of her visit by boat up the Mekong River to the town of Sadec where MD once lived, I knew I had to go. As luck would have it, I was already heading to China for a festival so it was easy to plan a detour on my way. My Indochine itinerary is thus — Hanoi to Saigon, from Saigon by boat up the Mekong River to Phnom Penh, then out to Sihanoukville to run a writing workshop. This will take in most of the towns where MD lived during the first eighteen years of her life — Hanoi, Phnom Penh, Vinh Long, Sadec and Saigon. Unfortunately I haven’t had much time for research so I will be flying by the seat of my pants, but that’s ok, it’s how I like to travel anyway.

I unpack a few things including a photo I printed from the web of MD as a young woman. She must be in her early 20s. Her dark hair is pinned up, drawn back from her forehead in the style of the time; eyes downcast, directing the viewer past the dainty nose to her dark red lips. She wears a collarless jacket: thin white stripes on black or blue, and a striped blouse with a loose tie at the throat, held in place by a Diamante brooch. A strand of hair escapes her right ear.

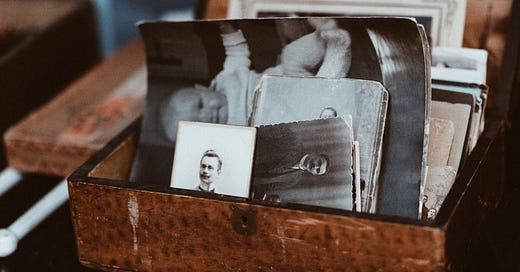

When I first discovered this photo I didn’t stop to interpret the expression caught between looks in a split second of time. The cupid bow lips and the wide forehead drew me in and shocked me with their familiarity. I knew I’d seen this visage somewhere before, but where? I immediately went searching under my bed for the mustard-coloured vinyl suitcase labeled ‘Old Family Photos KEEP!’ and found it right at the back, behind boxes of forgotten things I can never quite bring myself to throw away. I pulled the suitcase out, brushed off the dust and fluff, unbuckled its vinyl strap and opened it up to the precious photographic heirlooms cradled within. Gently removing the wrappings, I peeked in at each diorama of the past, resisting the urge to pull them all out for a proper look as I usually did. A marker in my memory told me the one I wanted was near the bottom, nestled among shards of glass from a breakage I meant to clean up last time I visited this secret treasure trove. And there it was. A tinted photo of my mother Marjorie, wearing a similar style of blouse with the tie at the throat, sporting the same exposed forehead, same movie star lips as Marguerite. Only the eyes were different. My mother’s eyes stared directly at the camera with a look of resigned sadness that startled me.

It's dinnertime and I’m not hungry but I do want to make plans for tomorrow. But first I need to interrogate Mr TF again on the subject of MD. I re-negotiate the sloping stairs to the small reception area and from his stool behind the narrow desk Mr TF smiles his friendly smile, telling me of course he is happy to help.

‘Do you happen to know the location of the house of the French writer Marguerite Duras, where she lived as a young child ? I ask. ‘It would have been last century, long before you or I were born,’ I tease, ‘ around 1918, somewhere near a small lake. Surely it will have a plaque or sign like famous writers’ houses do?'

He gives me a blank stare. I say the name again slowly in my best French accent.

‘Marggaaaarreeete Duuuraaass.’

At last his eyes light up and from under the counter he brings up a folder and hands it to me.

‘Yes, yes, Marguerite, Marguerite,’ he says, nodding.

I open the folder and nestled in the plastic sleeves are brochures for a magnificent wooden junk, fittingly named Marguerite.

‘Halong Bay, Halong Bay,’ Mr TF insists, ‘you must go!’

I’d seen the iconic pictures of antique junks with yellow sails navigating the famous limestone islands and I recall my travel agent telling me it was an absolute ‘must do’. It’s tempting and I even want to say yes on the spot just to please him. Instead I tell him I only have a few days in Vietnam and will make my decision in the morning. Meanwhile I am on a mission to find ‘my Marguerite' in Hanoi. He gives a nonchalant nod of the head and puts the folder away. I bid him merci, bon soir and climb back to my airless cave. I make a few notes, set the air con on low and fall into bed.

In the middle of the night I wake to the picture of MD staring at me from the bedside table. I keep it in a scrapbook of photos I’ve collected of Marguerite and my mother Marjorie. I don’t know why I am so intrigued by their similarities and I’m hoping this trip will give me some clues. Born in the decade before the roaring twenties, their physical resemblance when young is uncanny and continues into old age. Although they lived in vastly different worlds, photos taken across the years bear surprising likenesses and even as petite old ladies they wore the same kind of peaked cap and dark rimmed glasses. They could certainly be sisters, although Marguerite had only brothers and Marj was an only child.

As bookend war babies neither had an easy entry into life. When Marguerite was only six months old, her mother was taken ill and sent back to France for treatment. She didn’t return for another nine months and Marguerite was left in the care of a Vietnamese servant boy. Similarly Marj’s mother Jeanie was seriously ill for the first years of her life and little Marjorie was looked after by her maternal grandmother, Granny Tonkin, who ran a boarding house called Penzance, in the small Victorian country town of Camperdown. A photo taken circa 1921 shows Marjorie aged three or four, in a Pollyanna dress and lace up boots, standing with her cousin in the street outside the house. Granny Tonkin is in the background, another grand-bairn in her strong arms. With a sick husband taken to his bed and a large family to support she took in lodgers and looked after everyone with the same cheerful kindness.

Another picture of Marjorie shows a knock-kneed girl of four or five, in a white embroidered dress and long white socks, holding a bouquet of chrysanthemums, her hair tied back in a big white bow, staring directly into the camera. Her intense gaze holds a look of wisdom beyond her years: a knowing determination, and even at this young age, the tinge of sadness that would follow her into adulthood.

Marguerite wears the same big floppy white bow in childhood photos taken in Vietnam. Long hair falls across her tiny shoulders as her large eyes interrogate the camera with a wary self-assurance.

How is it that a French girl born in a village near Saigon would not have looked out of place at the church fête in a country town in Australia? They could so easily be playmates, getting up to mischief behind the weatherboard shed where little girls of their age attended Sunday School, the wisp of mother's absence hovering over them like an invisible veil.

_____________________________________

*In her novel The North China Lover, MD uses footnotes as movie directions, notes on characters, extra bits of info and asides.

*It’s impossible to list the number of academic theses written on MD’s work. ‘Marguerite Duras became one of the most prolific and analyzed figures in 20th-century French literature and film.’ Robert Harvey and Hélène Volat, Marguerite Duras A Bio- Bibliography, publisher ABC-CLIO, LLC, 1997.

Well yes, glad to hear that Bill, was in two minds whether to dsiplay the photos at the end as I think as you say it's stronger without them. So will keep that in mind for the future. In fact I might even delete that double photo now. Thanks for your input!

Thanks Craig, great to meet you here. Yes, old photos, love them!