Looking for Duras weaves three strands of memoir into one: my lifelong infatuation with the French writer Marguerite Duras, a journey through Vietnam and Cambodia tracing her footsteps, and a musing on mothers and melancholy. (Read prev chap here or browse all chapters here.

We’ve left the Mekong tributaries behind but way out in the middle of one of the most famous rivers in the world, we are not alone. Whopping great ships, dredges, big old wooden boats, barges and all sorts of river craft are passing by. On the banks — factories, power plants, brick kilns, towns and cities spew bad smells and gunk into the river and the sky. It feels like industrialisation on steroids.

Mr Thao has emerged from his slump and sits up the front next to the driver, drinking guava juice and chatting. He also seems to be keeping an eye out on the surface of the water, for every now and then the driver pulls the throttle back and we stop dead — the reason why is never explained. It becomes a little more tricky when the setting sun reminds them, just as the New Zealand couple and I concluded, that we have no navigation lights. As darkness rapidly descends, the crewman sets to, fiddling under the dashboard with wires and screwdrivers and finally rigs up a hand-held light, which he shines about from the deck to spot floating debris and signal to big ships passing by. It’s clear that being on the river after dark is not part of their normal schedule. If it’s disconcerting, nobody shows it outwardly and within an hour or so, without incident, we arrive at our overnight accommodation.

The Floating Hotel is just as it sounds: a rather insalubrious two storey weatherboard hotel with rooms upstairs, bar and alfresco dining downstairs, all situated on a floating platform tethered to the riverbank. The view to one side looks into wooden stilt houses perched on the bank and to the other, across the Mekong. My room faces the shore, has a fan, a bed and that’s all you need really. I dine with the NZ couple and a German girl who loves to travel in Asia alone although all her friends think it’s strange. Eva and Bill, who must be well into their 80s, list their previous journeys and tell us they have been going on travel adventures every year since they retired. They decide the location of their next trip by pulling out a world map, closing their eyes and wherever their finger lands, is where they go. They’ve been to most Asian countries, some more than once and they always go budget because it’s much more fun.

Mr Thao is doing the rounds of the tables. The stress lines have left his brow and it’s the most attention he has given us so far. We invite him to join us and offer to buy him a beer. He declines the beer but sits down anyway. We make a few jokes about his rough day, but none of us press him for an explanation. He attempts a kind of apology to Eva and Bill.

‘Water under the bridge,’ Bill replies, ‘water under the bridge.’

The conversation gets on to the subject of ancestor worship after Eva asks Mr Thao if his generation still practice it. He explains that it’s simply part of life and that regardless of what religion you are, in each house you will usually find an altar for the deceased, where daily offerings of incense, fruits, and special sweets and prayers are made. When he was a kid he didn’t understand how profound this practice could be. But his father has traced their ancestors back several generations and made an altar in his house that places them in the centre of family life. It is not just for good luck or hoping the ancestors will protect you against misfortune, but for expressing gratitude for the part they have played in your very existence.

We tell him how it is more the habit of our culture to forget the dead than remember them. How we are encouraged to move forward, get on with our lives, get over the past. And to have photos of dead people on an altar in the centre of our house would seem a bit spooky. I think of my ancestors relegated to the dusty suitcase under the bed. How my kids don’t know what their great grandparents look like even though I have all their photos. Maybe I will bring them out for a viewing when I get back, invite family members over for a special dinner, celebrate their memory with some of the dishes they would have eaten back then. Tell the few stories about their grandparents that I know, such as Chas’s first posting to a one teacher school in Chillingollah near the Murray River and how he spent his holidays helping his uncles with the wheat harvest in the Wimmera, loading bags of grain onto old flatbed trucks to be carted away to tall silos standing like great giants on the hot, dusty plains. How as school kids in Ballarat, he and his mates would pile onto the back of the tram car and jump up and down in an attempt to make it come off the tracks.

Marj’s relatives were a lively lot too. Her grandfather was a stonemason and bricklayer from Cornwall. They got off the ship at Geelong, but were robbed of everything while travelling by horse and cart to Camperdown. Marj’s mother, Jeanie, used to ride a horse to school and loved life, but after her troubles while giving birth to Marjorie and her resulting long illness, Jeanie said on more than one occasion, she wanted to run away into the long grass. Did she suffer from depression too?

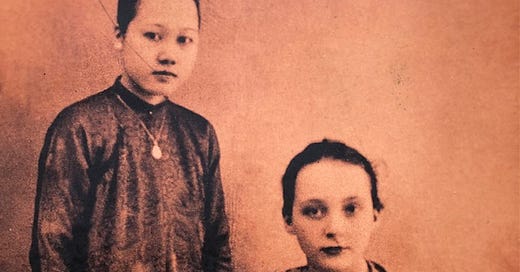

MD was estranged from most of her relatives. On her father’s side there was a rift between her mother and her father’s family who believed Marie Donnadieu was conniving to get her hands on her dead husband’s property which they believed should rightfully go to the sons of his first marriage. The closest relationship MD had with relatives on the mother’s side was via the studio photographs that Marie insisted they have taken on a regular basis. Marie would show them to aunts and cousins when she went back to France as evidence they were doing well. In fact the anti-social behavior of Marguerite and her brothers was so shocking to her relatives that it was easier to show them a photo than bring them along to a family get-together. Marguerite and her brothers couldn’t care less what the relatives thought and went along to the studio grudgingly. I’ve found surprisingly few of these photos online, although one in particular takes my attention. Marguerite around age 14-15, dressed in the traditional áo dài, is seated on a carved stool of the era while to her side stands a Vietnamese servant or friend also in a brocade áo dài, Behind them, shadows play on a tasteful blank studio backdrop (no fake Indochine scene). Marguerite wears dark lipstick and has her hair drawn back. It was later used on the cover of The North China Lover. The photo is obviously staged but the subjects are relaxed and convey such congeniality between each other and the place they find themselves in that it is hard to believe that MDs life in Indochine could be anything other than charming and pleasant. The purpose of the studio photo was fulfilled.

The mozzies are out in force. The Italian backpacker has invited the German girl for a drink at the bar and I take the lead from the elderly adventurers to retire early. I settle under my hole-filled mozzie net with the fan going full pelt and make a resolution, that like them, somehow I will find a way to travel until I drop. I manage to get off to sleep quickly but in the middle of the night I wake up from a dream. I am with Marj in a high-rise apartment in Manhattan. We are living there as mother and daughter and she is very old but not infirm. She is just back from the hospital but doesn’t seem worried about her health. We are moving about the apartment doing domestic things, being close and affectionate. I touch her gently on the arm and declare, ‘I will be with you until the end.’

I am thrilled that Marj has turned up in my dream and wonder how she found me all the way out here on the Mekong. It has been a long time since I had such a clear visitation from her. That’s what it feels like, although I know the dream has been triggered by the ancestor talk with Mr Thao. It all seems very positive and my declaration that I will be there for her until the end of time (my interpretation) moves beyond the realms of life and death. It’s more positive than another dream I had a while back — I am throwing some garbage onto a tall pile in the back yard and when something moving among the rubbish catches my eye, I take a closer look. To my horror I see it is Marj. Not sitting on top of the pile, but embedded within it, so that her face, hair and body are encrusted with growing organic matter. It was a brilliant image, like a wonderfully art-directed moment from a movie set in a supernatural Victorian era, but the message was confusing. She wasn’t dead after all (which was a relief) and she had been living so close to me I didn’t even notice she was there. Was I guilty of throwing her on the garbage heap or had I forgotten that she is an organic part of me?

In the final mental health crisis of her life Marj went cold turkey on her usual medication and stopped eating as well. She became so thin she had to be hospitalised which led to a new round of treatment —a milder, modernized version of electroconvulsive therapy, followed by some respite weeks in a nursing home in Melbourne. The home had a good vibe, was run by a lovely woman and felt homey and cosy. Marj had her own bedroom and adjoining sitting room and so we arranged for her to stay on. My sister was a couple of hours drive away and I managed to fly down from Sydney when I could. I accepted that the idea I had sometimes entertained, of one day bringing her to live with me, was never going to happen. My lifestyle had always been somewhat itinerant— I was living as a single parent, renting, sometimes sharing with another family and moving often. But I did want to give it a try and so I invited Marj to visit with me and my son (then thirteen) at my ex’s house in Newcastle while he was overseas for ten weeks. Juggling the elderly mother and the teenager had its challenges. Marj would be sitting on the living room couch as Louie and his mates came in after school to play video games and horse around. She didn’t complain much, other than to say they were a bit loud and though she had the option to retire to her room she usually stuck it out until dinnertime. She was no trouble really, except you could see she was in a state of perpetual nervous tension, worrying about every little thing. Most nights, around 3 am, she would come into my room to wake me up, telling me it was time to get ready for school. Or sometimes I woke to find her just bending over me, peering at my face. I would thank her, explain it was still too early to get up and lead her gently back to bed.

In the mornings, after we got Louie off to school, I would sit at the kitchen table to write and she would lie in. Later over cups of tea and snacks we would chat and I wish I could remember now what we said. Sadly it wasn’t the old Marj I was conversing with and I could see that behind her polite repartee she was trying to work out how to escape. She was no bother really, but she needed looking after around the clock. When it was time to take her back to the nursing home in Melbourne, my brother happened to be driving south from Queensland, so we arranged to meet up at a service station along the Pacific highway. We bundled the precious cargo of our little Marjorie Mum out of one car and into the other. It was going to be a ten hour drive so we leaned the passenger seat back and made her comfy with pillows and blankets in the hope she could sleep or at least close her eyes to the worries that constantly plagued her. Anyone watching may have thought we were acting out a nursing home escape. In a way we were, but at the end of the ten weeks I realised as Marj had always known, that my fantasy of caring for her until the end was just that.

A couple of night birds call out from the shore. It takes me a while to get back to sleep but I don’t mind. I replay the details of the dream, happy to know she is ok.

After an early breakfast offering of greasy eggs and sweet white bread rolls, we board our boat and are soon out in the middle of the river again, heading for the Vietnam/Cambodian border. All the the water traffic that was around us the day before, slowly disappears and soon the waterway is wide and empty. By the time we get to the Vietnam checkpoint, there’s only a couple of other tourist boats and us. We reach the left bank and disembark onto a floating immigration office that has a small café selling soft drinks, machine coffee and cup noodles. Mr Thao gathers our passports and takes them through a door into an office. On a deck overlooking the riverbank we crowd onto white plastic chairs and wait. The formalities seem to take forever but when our passports are finally returned and we shuffle back to the landing, we realise it’s time to bid our Vietnamese guide goodbye. I want to shake his hand but he is busy supervising the luggage transfer onto our Cambodian boat, which is a carbon copy of our Vietnamese barge. And in a flash he is gone. Like the exit stamp on my Vietnam visa, it seems too final, and my time in Vietnam too short.

Hi Jan, I’m enjoying your floating travels, dreams and memories as the swirl through your story.

Will do when I get back.